MIT just Published the First Brain Scan Study of ChatGPT Users & the Results are Terrifying

AI isn't making us more productive, it's making us cognitively bankrupt

We live in an age of unprecedented technological assistance. Tools like ChatGPT can draft emails, write code, and brainstorm ideas in seconds. This convenience is powerful, but a groundbreaking study from researchers at MIT and other institutions asks a critical question: What is this convenience costing our cognitive muscles?

In a comprehensive study titled "Your Brain on ChatGPT," researchers explored the cognitive and neural impacts of using AI for a common educational task: writing an essay. They divided 54 participants into three groups:

The LLM Group: Used ChatGPT (an advanced Large Language Model) as their only resource.

The Search Engine Group: Used Google search, but without AI-generated summaries.

The Brain-only Group: Used no external tools, relying solely on their own knowledge and thoughts.

For four months, participants wrote essays under these conditions while their brain activity was measured with EEG, their essays were analyzed with NLP, and they were interviewed about their experience. The findings paint a startling picture of a trade-off between short-term ease and long-term cognitive engagement.

Everything I’ve Written, One Button Away With 40% Off

I have created a bundle for my books and roadmaps, so you can buy everything with just one button and for 40% less than the original price. The bundle features 8 eBooks, including:

1. A Tale of Three Brains: How We Think When We Write

The most striking discovery came from the EEG data, which measures the communication between different brain regions (neural connectivity). The researchers found a clear, hierarchical pattern: the more external support a participant had, the less their brain networks fired up.

The Brain-only group showed the strongest and most widespread neural connectivity. Their brains were a bustling city of neural activity, with regions responsible for memory, semantic processing, and executive control working in close coordination.

The Search Engine group showed intermediate levels of brain engagement.

The LLM group exhibited the weakest overall connectivity. While their brains were still active, the complex, widespread networks seen in the Brain-only group were significantly quieter. This suggests that the AI was offloading much of the heavy cognitive lifting involved in generating, structuring, and refining ideas.

This figure shows the differences in brain connectivity (measured by dDTF) for the Alpha band, which is associated with internal attention and semantic processing. The "Brain-only" group (bottom row of brains) shows significantly more and stronger connections (thicker, redder lines) compared to the "LLM" group (top row), indicating much higher neural engagement. The scale on the right shows that higher p-values (more red) indicate greater statistical significance.

2. The Behavioral Cost: "I Wrote It, But Do I Remember It?"

This difference in brain activity had tangible consequences for memory and ownership. The researchers asked participants two simple questions after each session: "Can you quote a sentence from the essay you just wrote?" and "How much of this essay feels like yours?"

The results were stark. In the first session, 83% of the LLM group participants could not quote a single sentence correctly from the essay they had just finished. In contrast, only 11% of the Brain-only and Search Engine groups had the same difficulty. This "quoting deficit" suggests that when using the LLM, the content was not being deeply encoded into the participants' memory.

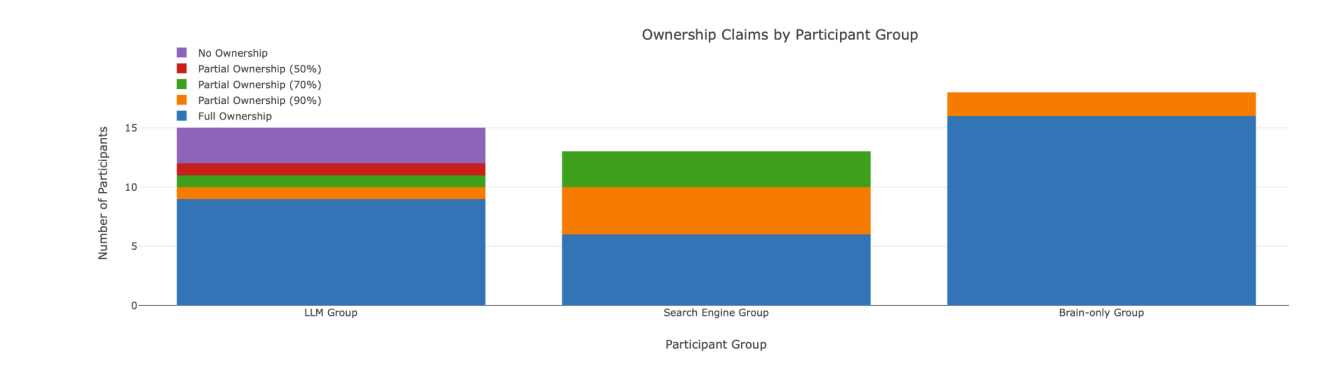

This disconnect also appeared in how participants felt about their work. The Brain-only group almost unanimously claimed full ownership of their essays. The LLM group, however, was fragmented, with many feeling like they only owned parts of the essay, or in some cases, none at all.

Figure 2 shows that the vast majority of LLM users struggled to quote from their essays, a task their peers in other groups handled with ease.

While Figure 3 illustrates that the Brain-only group felt near-total ownership, a significant portion of the LLM group felt only partial or no ownership of their work.

3. The Cognitive Debt: What Happens When the AI Is Taken Away?

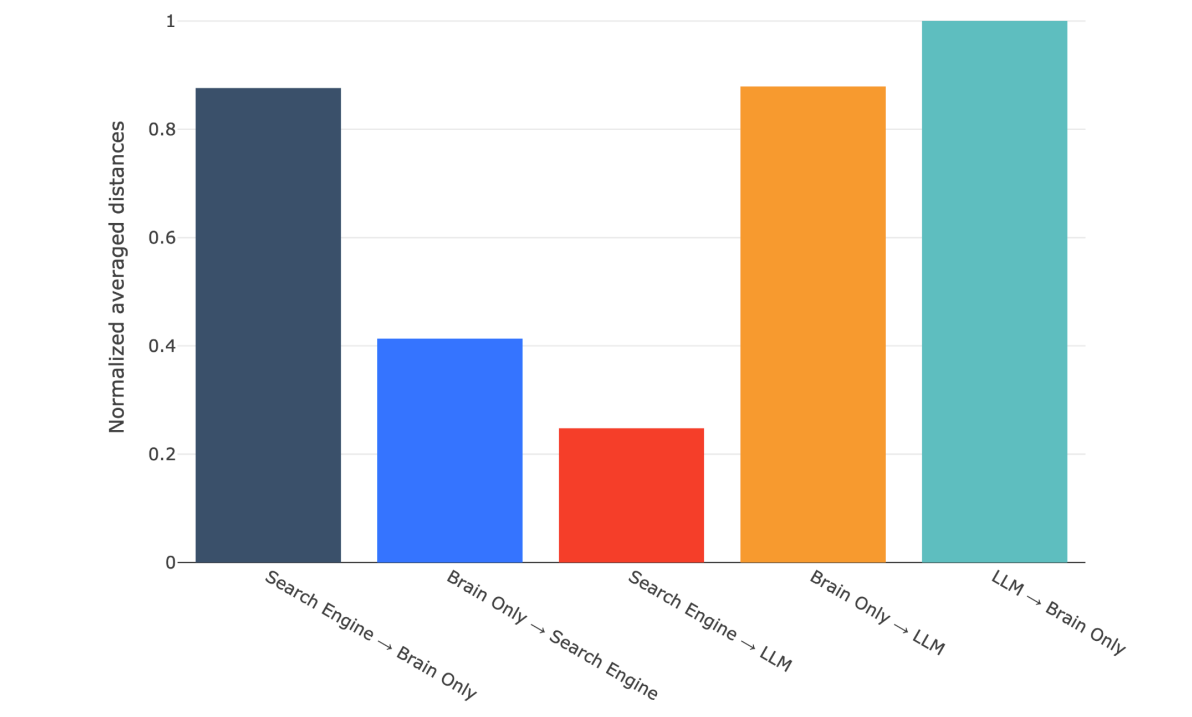

The most fascinating part of the study came in Session 4, when the researchers switched the conditions. Participants who had previously used the LLM were now in the Brain-only group (LLM-to-Brain), and vice versa. This revealed what the paper calls an "accumulation of cognitive debt."

The LLM-to-Brain participants, now writing without their AI assistant, struggled. Their brain connectivity was weaker than that of the participants who had been practicing without tools all along.

They had not built up the same cognitive "muscle." Their writing style also changed dramatically, becoming much less similar to their previous AI-assisted work, indicating a heavy reliance on the tool's structure and phrasing.

Conversely, the Brain-to-LLM participants—who had been writing on their own—used the AI as a powerful tool for enhancement. Their brains showed a massive spike in connectivity, suggesting they were actively integrating the AI's suggestions with their well-practiced internal thought processes. They weren't just copying; they were curating, comparing, and directing.

This chart shows the normalized distance (i.e., how different the essays were) between Session 4 and previous sessions. The tallest bar, "LLM -> Brain Only," indicates that participants who lost their AI assistant produced essays that were significantly different from their previous work, highlighting a dependency on the AI's style and structure.

This study does not argue that AI tools like ChatGPT are inherently "bad." Instead, it suggests they create a critical trade-off. They offer a shortcut that can make tasks easier and faster, but this convenience comes at the cost of the deep cognitive engagement that builds long-term skills, strengthens memory, and fosters a sense of intellectual ownership.

The "cognitive debt" is real. By allowing us to bypass the effortful process of thinking, these tools may prevent our brains from building and strengthening the neural pathways essential for independent thought and creativity.

The study powerfully concludes that the path to true learning and mastery still requires us to do the hard work ourselves. The key, it seems, is to use AI as a scaffold to build upon our own ideas, not as a crutch to replace thinking altogether.

This one hits hard. The “cognitive debt” you describe feels familiar — I’ve seen myself, in how easy it is to skip the hard part of thinking.

I’m actually working on something that tries to offer an antidote: a framework I call Reflective Prompting, a way to work with AI that protects ownership, sharpens memory, and keeps thinking human-first.

Thank you for this important blog post